Standing Like a Tree

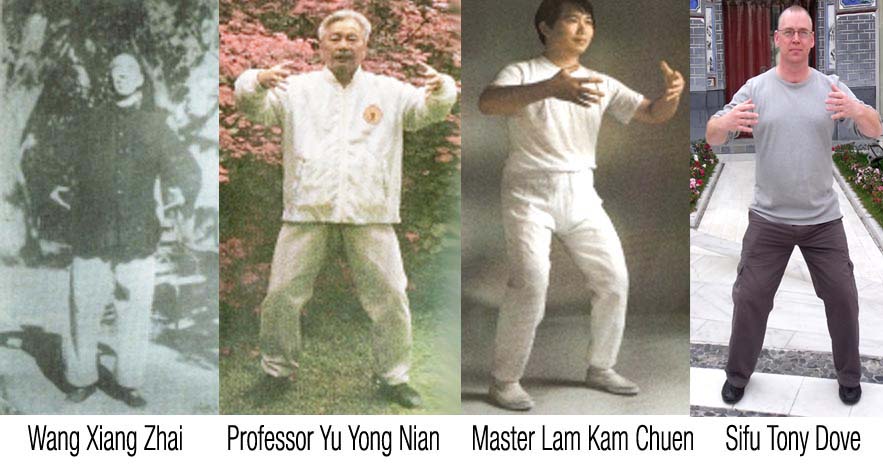

"The ordinary is the extraordinary! " ~QIGONG MASTER WANG XIANG-ZHAI

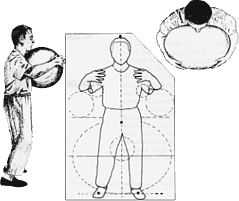

Standing Meditation is the single most important and widely practiced form of qigong, integrating all elements of posture, relaxation, and breathing previously described in class. It is a way of developing better alignment and balance, stronger legs and waist, deeper respiration, accurate body awareness, and a tranquil mind. Standing Meditation is just what the name implies; one meditates while standing, holding the arms in a rounded position, as though embracing a sphere, and observing the natural flow of the breath. The Chinese term for Standing Meditation is Zhan Zhuang, “Standing Post.” One learns to stand as still and stable as a wooden post in the ground. Standing has several advantages over seated or supine meditation. The mind is more likely to remain alert, as any lapse in awareness might cause one to lose balance. In Standing Meditation, the legs and feet are naturally extended, uncrossed; thus blood circulation is not impeded and may actually improve.

Most importantly, in Standing, the body is always part of one’s experience. Meditation does not become an exclusively psychological or spiritual practice. Through the practice of Standing Meditation, we learn how to unify the body and mind so that every activity is savored with the whole being.

HOW TO PRACTICE STANDING MEDITATION

General Points

The most important points to remember are: The body is relaxed, yet extended and open. Use minimum effort. Stand with the feet parallel and shoulder-width apart, the toes pointing straight ahead, the knees slightly bent, the back straight but not stiff, the abdomen relaxed. The head is held as though the crown is suspended from above. The shoulders are relaxed downward and the arms hang loosely at your sides.

Position of the Feet

The weight is evenly distributed on the feet (spaced the width of one’s shoulders, toes pointed straight ahead). Make sure you are standing plumb erect, not leaning to the front, back, right, or left. This will allow the body’s weight to spread through the feet into the ground, favoring neither toe, heel, inside of the foot, nor outside of the foot. Maximizing contact with the ground creates a feeling of deep roots, easy balance, and abundant internal energy, qi. One feels like a tree, drawing nutrients from the soil. The posture should feel relaxed, harmonious, and natural.

Position of the Arms and Hands

When first beginning, let the arms hang loosely down the side of the body (just as in the Tai Chi preparatory posture). As you become more advanced, the arms are in a rounded position, at the height of either the abdomen, chest, or face, as though lightly embracing a giant beach ball. The palms can be facing either away from or toward the body.

The height of the arms can vary according to your ability. If you have a condition that prevents lifting the arms to shoulder height, practice with the arms in a comfortable position, below chest level. If you are disabled, apply all the principles of standing to your seated position in a chair or wheelchair. If the arms cannot be lifted at all, let them rest on the lap. You can still drop the breath and imagine a deeper, more alive connection with the ground.

Keep the shoulders and elbows relaxed (just as the Tai Chi principle sink shoulders, drop elbows). The fingers are gently spread, the palms feel hollow and receptive. Try to keep the forearm, wrist, and back of the hand in an almost straight line or curving gently. Avoid letting the hands droop down toward the wrists or flex back stiffly toward the forearm. An excessively open or closed wrist joint interferes with the flow of qi and blood to the fingertips.

The Eyes

The eyes should be open and relaxed, looking with a soft focus, straight ahead into the distance. You are seeing everything but not focusing on or grasping at any external object. You see in an unattached way so that you are not distracted from your inner awareness.

The Breath

The breath is completely natural, relaxed, and diaphragmatic. With every inhalation, feel the lower abdomen gently expanding. With every exhalation the abdomen retracts. Don’t force the breath, just feel its natural rhythm. The breath should be tranquil, long, and fine. “Fine” means smooth and even, as opposed to coarse and broken.

Concentration

Simply be aware of whatever presents itself to consciousness. This may include feelings of comfort or discomfort, muscular tension or weakness, the rhythm of the breath, thoughts, or emotions. Give yourself permission to feel, without either prolonging or rejecting whatever occurs. The goal is to cultivate a state of clear perceptiveness, without exclusively focusing on any particular, passing event.

Use the breath as your focal point. Whenever your mind begins to wander, gently ask yourself, “Am I breathing? How am I breathing?” Bring your attention back to your breathing. Physiological awareness brings self-awareness. The mind becomes silently attentive to the subtleties of what is happening in the here and now, rather than thinking about the past, the future, or abstractions disconnected with the present.

Time and Length of Practice

Standing can be practiced at any time of day, but early morning is best. The following recommendations are based on the assumption that you are in relatively good health. Do not stand as long as recommended here if you have a joint problem, such as arthritis or any other condition that makes it medically inadvisable to practice Standing for extended periods.

Begin training about five minutes a day. During the first week, let the arms hang loosely down the side of the body. When (and if) you begin practicing with the arms at the height of the abdomen, chest, and face, divide the time evenly among the postures. During your second week of training, practice for ten minutes a day, fifteen minutes per day during the third week, and so on. Build gradually to a minimum of twenty minutes daily Standing, and a maximum of forty minutes. This is a small investment of time considering that you will probably have more energy during the day and need less sleep at night.

Proceed slowly and systematically. After three to four months of regular training, you will be able to sense the most beneficial length of practice. In qigong, “beneficial” does not necessarily mean comfortable or easy. It does mean a length of practice sufficient to deepen self-understanding and to improve health and vitality. The period can vary a great deal from person to person. Standing is like eating. Some people need a lot, some a little to satisfy them.

Concluding Your Session

At the end of your Standing Meditation session, let your hands float down to your sides, and allow them to rest against your thighs. Pause momentarily while you breathe naturally and relax. Gently exit your standing posture and move around a little. You are ready for the next stage of your Tai Chi practice or for the day’s activities.

Difficulties and Challenges

Standing Meditation is the optimum posture for balanced flow of qi (thus it is the beginning posture for Tai Chi). As a result, all of the places where qi is not flowing come immediately into the foreground of awareness and are experienced as discomfort. One notices places of tension, weakness, constriction, disease. For instance, if your shoulders are chronically raised, after only a few minutes of Standing, the shoulders may ache and feel so elevated that you feel they are touching your ears! If the thigh muscles tense beyond what is necessary, they will soon “burn” with the effort of Standing. If your sacral vertebrae are misaligned, you will really know it when you Stand!

Standing does not test how strong you are, but rather how intelligently you use your strength. Discomfort reveals places of dysfunction and should be welcomed as an opportunity for improvement. When you experience it, do not immediately change your posture. You may feel like shaking, wriggling, or moving your arms, legs, or torso. If you do so, you will lose the opportunity to discover, through your attentiveness, how you are tense.

When you find an area of discomfort, apply either of the following strategies:

1. Do nothing – simply being aware of tension may change it.

2. Think of the tension or discomfort dropping down, through the feet and into the ground.

If Standing becomes painful rather than uncomfortable, then do not continue. Pain is a danger signal and should not be ignored. If the pain is a result of poor postural habits, it may have a simple solution, such as checking if the back is straight, the chest relaxed, etc. If, however, it is a result of a medical disorder, it should be treated by your physician and Standing resumed only with his/her permission.

Stages of Standing

Most students pass through three tests in Standing Meditation. First, there is the “test of discomfort,” where every joint and muscle seems to be out of place or doing something wrong. This is often accompanied by trembling or shaking in the joints, most frequently in the ankles, knees, or wrists. Trembling results from weakness in the muscles or tendons; perhaps certain muscles have weakened or atrophied because of lack of use. The body is adapting to a greater charge of internal energy. Neither reject nor exaggerate such shaking. Just feel it, and if, after a few minutes, it does not stop of itself, gently end your Standing practice and resume it again at a later time.

Test number two is called “the test of fire.” Finally, after months of practice, one has learned how to release energetic knots and tensions.

The basic body mechanics – how to stand and breathe – are automatic. The places that were formerly depleted are now filled with qi. The hands and feet may feel uncomfortably warm. The forehead is beaded with sweat. The abdomen feels hot. Again, this is a transitory test that may last anywhere from a few days to a few months.

The most difficult test, number three, is called “the test of patient growth.” It is at this point in one’s training, when Standing feels ordinary, comfortable, and nothing special, that most students abandon the practice and look for a new form of “entertainment.” But it is precisely at this stage that the most lasting benefits of Standing are cultivated. The ordinary is the extraordinary. One can now focus not on unusual sensations, symptoms of imbalance, but rather on the positive, on the miracle of breathing, feeling, and awareness.